I move the VHS tape with me to every new apartment, packed away in a cardboard box full of my old things. A home video documenting a family trip to a pumpkin patch in the sprawling farmland outside my childhood hometown more than three decades ago. In the video, I’m a little boy maybe four or five years old in a blue jacket walking hand in hand with my father between rows of giant pumpkins all lined up in a freshly mown field, trying to find the perfect one to knife into a jack-o’-lantern later that night with my mother at our new house.

My father has a belly already round from too many beers, the fingers of his left hand curled at odd angles after the accident years before while driving home from the bar. I don’t remember him without a beer can close at hand. He might have been holding one in the video.

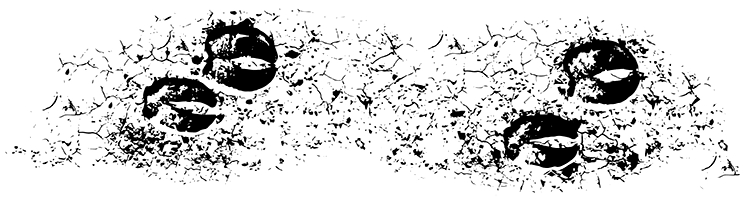

I make a show of trying to lift up some of the largest pumpkins, almost like I’m trying to impress my father, sometimes stumbling backwards from the effort and causing him to burst into laughter before helping me up from wherever I’ve fallen. At the end of the video, the ground beneath my feet is strewn with newly fallen autumn leaves as I stand next to a scarecrow and pick at the straw of its chest, the red flannel shirt affixed to its makeshift body billowing lightly in the breeze. “He doesn’t have a brain,” I say, remembering The Wizard of Oz.

My father later lived in our new house alone after the divorce, after the night when I was only six years old and I found him with his fists raised above my mother in the kitchen. I don’t know if I made a sound when I ran toward them, but suddenly I was between them, standing in front of my mother to block her from my father, facing him down like I thought a man was supposed to do. My father’s face was red and angry, his eyes unfocused and far away, a sour smell to his breath. His one good hand was already in a fist, and the blow my father had intended for my mother stopped just short of my face, his hand floating there before me like something coming down from the sky, from outer space, from somewhere none of us had ever been.

I instinctively folded myself into my mother’s arms just as my father stumbled backwards in the other direction, blinking away his confusion and then silently walking back to the master bedroom at the end of the hallway. The last thing I remember about that night is the feeling of my knees buckling and landing hard on the kitchen floor just after my father went away, the tiles cold on my skin through my thin pajamas, pain searing up through my body as my thin bones ground against the hard cheap tile.

My mother continuing to sob, her face now buried in my neck, her arms tight around my chest and back like I would float away if she ever let me go.

She had had to wake me up that night with her screams. But in the home video shot just before Halloween, only a year or two before that night, my father protects me. He lets me run into his arms away from a mechanical witch when I stumble upon her lair in the shadowy doorway of an old red barn, stirring the contents of a massive black cauldron with a metal arm mostly concealed by a long black robe. The sight of her pointy hat and bristly broom send me into trembling hysterics, my thin and nervous body seized by fear. And my father holds me close to his chest when I thrash and cry out at the sound of the evil cackle bursting out too loud and tinny from the speaker that must have been lodged in her throat, hushes me and presses my wet cheeks against the stubble of his beard.

I like the near obsolescence of the old VHS tape, how it can’t be easily watched. After all, I haven’t actually seen it in years. And I haven’t ever tried to convert it to a more contemporary format because the distance I have from it now allows me to trust my memory of it, as far as you can trust a memory.

I like my memory of the video because it’s the only time I’ve ever seen how my father and I were together. He drank himself to death before I became a teenager, died on the side of the road on his way home from a bar, and we’d long stopped recording home videos by then anyway. But the video was the only time I could’ve ever seen the way he looked at me when I didn’t know he was watching. The only time I could see myself the way he saw me, that serious and frightened little boy kicking his way through fallen leaves.

My father probably could tell even back then that I’d soon be needing a kind of protection that he wouldn’t be able to offer me. Those years as a queer boy in the closet. There was the kid in the old neighborhood who I’d watched one summer, followed him down the sidewalks and waited outside his house for a glimpse of him through the window. The rage in his face when he shouted at me to leave. And then the older boy from down the street when I was only twelve years old, the sharp kick delivered square to my chest after we shared a bottle in his basement and the booze had made plain what I wanted from him.

Later, those men who would eventually visit me where I’d been hiding, where I thought no one could see. Men who noticed me for what I was and didn’t pretend they hadn’t. A boy afraid of something in himself and men who knew he’d do anything they asked, if only they wouldn’t tell. If only they would keep the secret of him.

I liked seeing myself afraid of the witch in the old home video of the visit to the pumpkin patch, because I liked seeing my father rescue me—liked the way something in my face changed when I knew I was safe. At least I like remembering it that way.