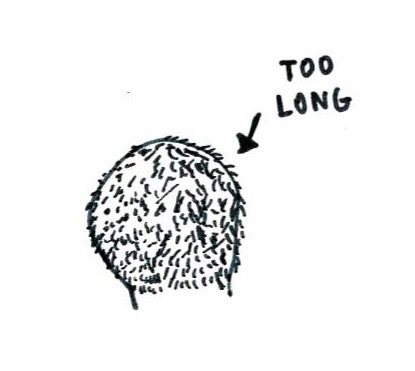

Michael has awesome hair. Here is Michael, my husband, from many many years ago. See how great his hair is?

Admittedly, he has less hair now. Particularly at the very top. But he still has awesome hair.

About two months before our baby was born, I decided that Michael needed a haircut. Part of his work involved attending a legal seminar which he needed to attend the next day, and his hair was starting to look a little scruffy. As well, Michael has Cerebral Palsy, so little things like a sharp haircut can help mitigate unideal first impressions about his disability. We also had a dinner party that night, and I wanted Michael to look good.

However, pregnancy had been hard on our finances, and things would only get harder with a new baby.

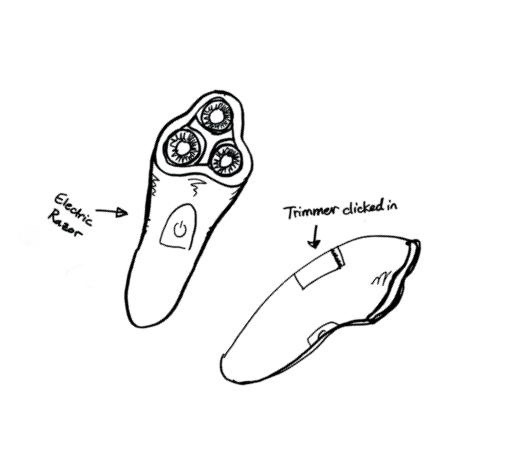

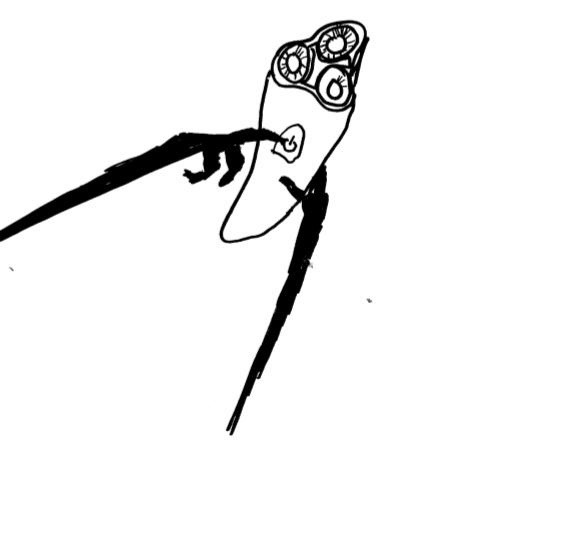

I determined that, although I was no professional hair cutter, it was best if I gave Michael a haircut. This would let us save twelve dollars. I was even more encouraged by the fact that Michael had received an electric razor for Christmas that included a trimmer on the back:

The trimmer would, of course, make hair cutting a breeze, as I could shear a head full of locks much more quickly than with scissors, thus bypassing the need to manually operate one stroke at a time.

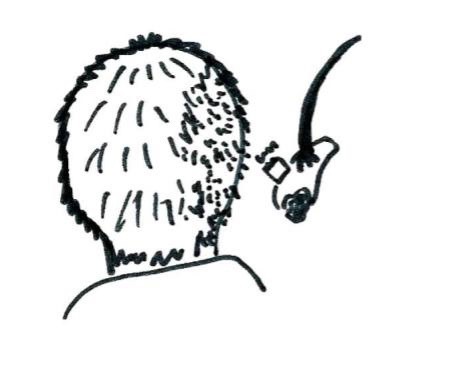

So I started to cut Michael’s hair.

It wasn’t the most even job, but I figured I could fine tune it after I had finished cutting the bulk of it.

Unfortunately, I kept on shearing some hair shorter than the rest.

So I kept on trimming.

In the course of this, it became apparent that my confidence in the trimmer as a hair cutting device may have been misplaced.

Michael’s hair, by now, was so short and uneven that I didn’t know how to salvage it, and we had the dinner party that we were supposed to be leaving for in half an hour.

Intent on solving the problem as neatly and quickly as possible, I then reasoned that the trimmer, which had, in fact, never been designed for cutting scalp-rooted hair, would work better if I used it in a way more akin to its purpose as a beard trimmer.

The trimmer itself was on the end of a sturdy plastic flap that was a few millimeters wide. Since the initial problem was one of length consistency, laying the plastic flap on its side presented itself as a clear fix. This would have the less-than-desirable effect of producing a buzz so short that, from a distance, one might miss the fact that Michael had hair at all. But, on the other hand, that was still a slightly better outcome than looking as though a particularly fierce dog had acted its vengeance on Michael’s hair.

I asked Michael if he would be terribly upset to have a buzz-cut, which he was fine with, and tried a corner of his scalp.

It wasn’t quite a perfect buzz—the plastic flap had a curve that made it wobble a little—but it seemed tolerable, and was at least preferable to the state his hair was already in.

In fact, it may have turned out alright if the story ended there—a slightly wobbly but forgivably so buzz cut.

The razor had sputtered and shut off.

I tried plugging it in the outlet, which I probably should have done from the start instead of relying on battery power.

It refused to turn back on.

This was too much for me to endure, and I crawled to the floor, emitting high pitched gasps.

As my fight-and-flight response kicked in after my initial play-dead reaction, I started to stumble around the apartment in search for scissors, upending baskets and opening drawers until I found a small pair of sewing scissors.

I looked at Michael and said, “I have to finish the buzz cut.” He sat down in the hair cutting chair.

I remember giving myself a haircut as a three year old. This was much, much worse.

Unlike a proper hair buzzer, sewing scissors are simply incapable of cutting each individual hair at the exact same length, because the motion of the blades inherently brings various hairs close together in a bunch, and the distance between a hair at an angle and a hair straight up cannot be equal.

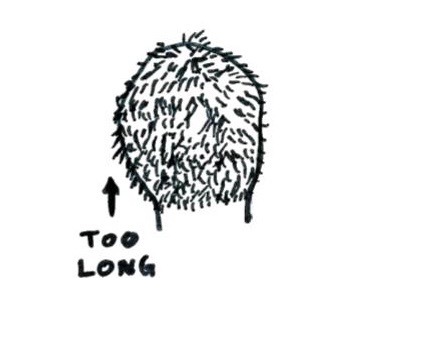

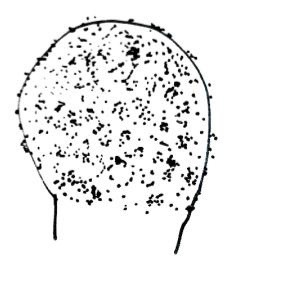

The final product looked far worse than anything I can replicate. Here is a poor approximation:

I don’t know what I would have done without Michael, other than the fact that the ordeal wouldn’t have happened in the first place. He held me while I sobbed, and said “don’t say that” when I said that I would never cut his hair again, and he put my hands on his head when I said I shouldn’t be allowed to touch his hair, which made me sob more.

Eventually he pulled me up, insisting that his friends wouldn’t mind his haircut or that we were late for the dinner party, and we stopped at a store to buy a hat, which our dinner host complimented and which Michael pulled off—trying to be discreet—during a blessing on the food.

At seven the next morning, we went to a hair salon where (mercy of mercies) the kind stylist didn’t ask what happened to Michael’s hair. She gave him a proper buzz on the shortest setting possible, so that he was allowed to attend his seminar and continue his week with at least some dignity.

A week later, we had plans to meet up with Michael’s Grandma, a lively and quick-witted and compassionate woman. She was in the middle of chemotherapy for breast cancer remission, twenty years after she first got it. She wore a wig, and I missed her old hair with an ache.

That day, I still felt crushed and defensive over Michael’s slightly splotchy near shave. I would for weeks, until it started to grow out, and then I wanted to forget about it as soon as possible. But Michael’s grandma was kind, and she was hurting far more deeply, and when she saw Michael’s abrupt cut, she smiled and said, “that’s what my hair looks like. Except less,” and I wanted so much to see her precious scalp speckled with bristle.